Bernadette Corporation, Hugo Blomley, Charles & Ray Eames, Thomas Miller, Meg Porteous, Gemma Topliss, 'Limbs of a Yacht'.

28 Jan - 8 Feb 2023

Tommy Atkins was first used as a generic placeholder name by the British Empire in their official ‘how-to’ manuals, published to encourage voluntarism in the early stages of WWI. But, on the ground and in the trenches, this bureaucratese took on a life of its own; when German forces catcalled “Tommy Tommy Tommy” to provoke movement from human shields dotted across the sprawling swathes of no-man’s land, their interpellation strengthened it with the force of a proper name. Not to be outdone, imperial versifier Rudyard Kipling reclaimed the slur in his collection Barrack Room Ballads, and here ‘Tommy’ entered the popular imagination as the ‘Saviour of 'is country when the guns begin to shoot’. This anonymous ‘Tommy’ — equal parts idea and flesh — was manufactured out of the vanishing point between agency and function: man and weapon, humanity and fodder, reality and poetry.

We can now see him stretched through the gallery, surrounded by his detritus and afterlives. The latest group show at Asbestos, ‘Limbs of a Yacht’ interrogates this same vanishing point by orienting itself around one of its classic symbols: the prosthetic. Designed for restoration and enhancement, the prosthetic must always be a process and product, it is the crowning jewel of the graft made between trauma and the monotony of the everyday. But if it is in the very nature of the successful prosthetic to confuse these two temporalities, then which came first, ‘Tommy’ or the gun?

At this point it seems hard to remember. Just as Thomas Miller’s, a.k.a Tommy Gunn’s, punning moniker unintentionally constellates some of Asbestos’ curatorial concerns, his A4 collage Sandra Good, which sloppily plasters empty Lyrica, Valium and Endone trays around an eerie childhood photo of prominent Manson Family member ‘Blue’, stages the most didactic dissolution of the distinction between reality and its artificial stimulants; we enter the prosthetic’s dream. In Hugo Blomley’s Untitled ‘hole-in- the-wall’ sculptural relief, gluts of coagulated plaster are impressed with textured marks. Are these traces of the desperate sweat seeping from a hand grasping for its weapon too late? Or the imprints left by the gun on the dead body it was violently pried from? Both works present a memento mori at once artefactual and anthropomorphic.

But maybe ‘Tommy’ survived. Maybe he hobbled away with the aid of a moulded plywood splint replete with soft contours and planer warping, designed by doyens of post-war Californian industrial design Charles and Ray Eames. The Eames splint was widely lauded as a more sympathetic and stylish approach to the nasty business of disfigurement. Yet the designers’ realisation that they could stop the spread of gangrene by strapping disfigured soldiers directly with their new American dream was only the beginning of a journey in prosthetics. The funding they received from the US Navy launched their furniture empire, famous for chairs which were moulded especially for the supple torsions of a human frame subjected to extended watchkeeping shifts in loungeroom trenches.

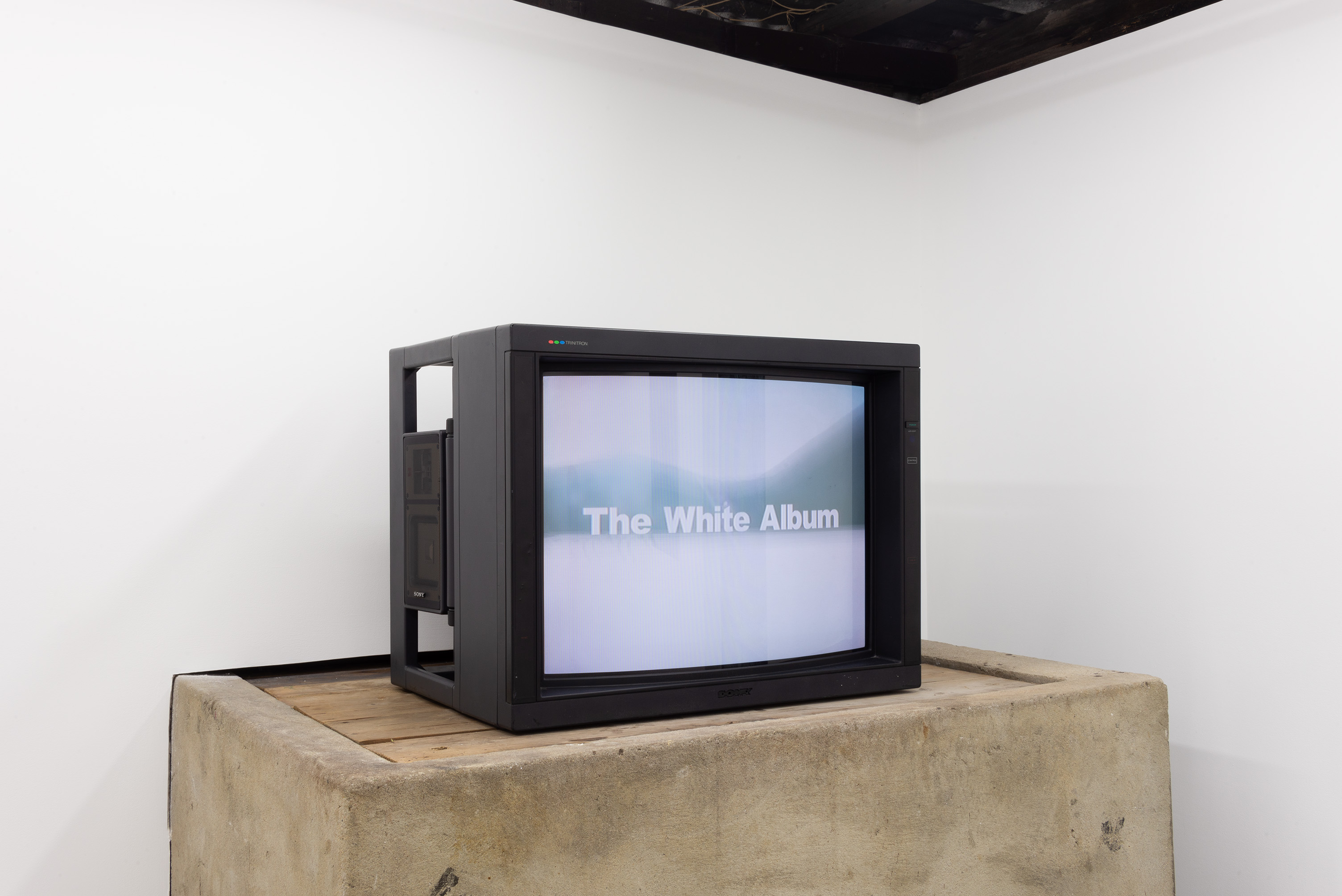

Bernadette Corporation’s video work Hell Freezes Over returns us to no-man’s land — (upstate New York) — splicing Sylvère Lotringer’s rambling lecture on symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé with haute couture fashion shoot. An icon of poetic concentration and purification, Mallarmé has long been instrumentalised as a tragic point of identification for the burnout of the artwork into theory and the disintegration of that theory into vacuousness. As Lotringer whips himself into a frenzy, high off his own supply, a chic model stares dumbly out of aviators so scratched they appear frosted. They both float like astronauts through a china-white world, consumed by the drunkenness of things being various.

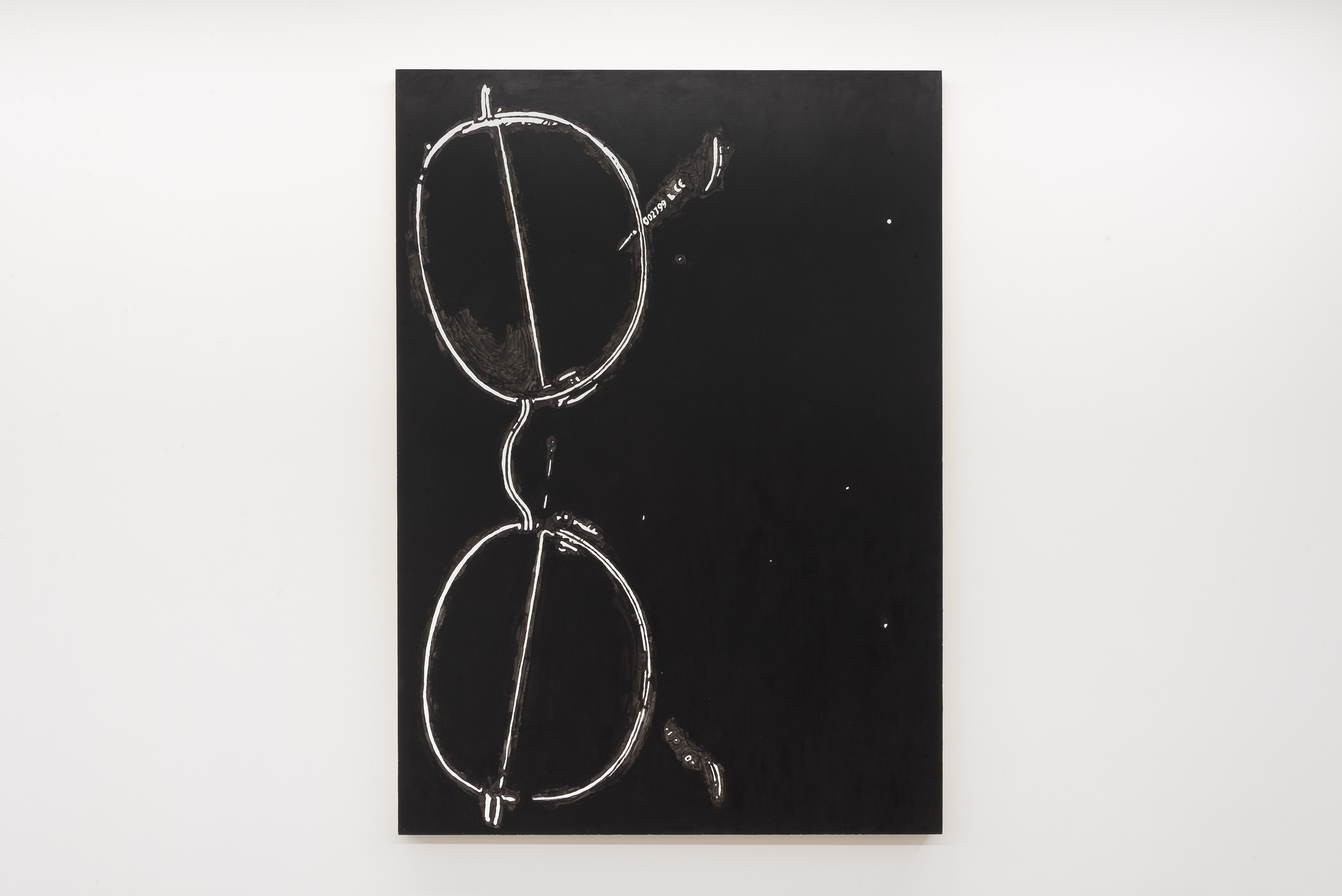

Gemma Topliss’s Glasses continues this ‘spectacle’ but fades it to black. Absurdly blown out, her turn to the iconographic first appears as a satire of the toy town art world, transposing a ubiquitous accessory onto the scale of a sacred idol. But moving closer to painting, flecks of white paint seem to fall softly from above, spawning snow, perforating the heavy acrylic coat with invasive spots. The temporality of the painting shifts. The glasses are folded, creating a chiasmus which shudders through the negative space of the picture-plane, revesting the ancient link between religious icon and ‘enhanced vision’ in the garb of the prosthetic. Alongside, Meg Porteous’ Drive 3 offers a dusty tableau of the erotic mainline coursing through the modern imagination; scarred and scudded leather undercut with a scintillating glimpse of pantihose. And yet the foot is only resting on the accelerator. The motor of the Mazda fails at the moment of ignition.

This exhibition hovers, a patchwork of black squares paralysed and impotent under the fluorescent gallery lights. Mallarmé once said that art is ‘the subject to which everything is attached’. ‘Limbs of a Yacht’ uses the prosthetic to restage the tensions faced by the artist and the artwork as they oscillate between process and product, squaring elation with dejection; this is Asbestos attachment theory.