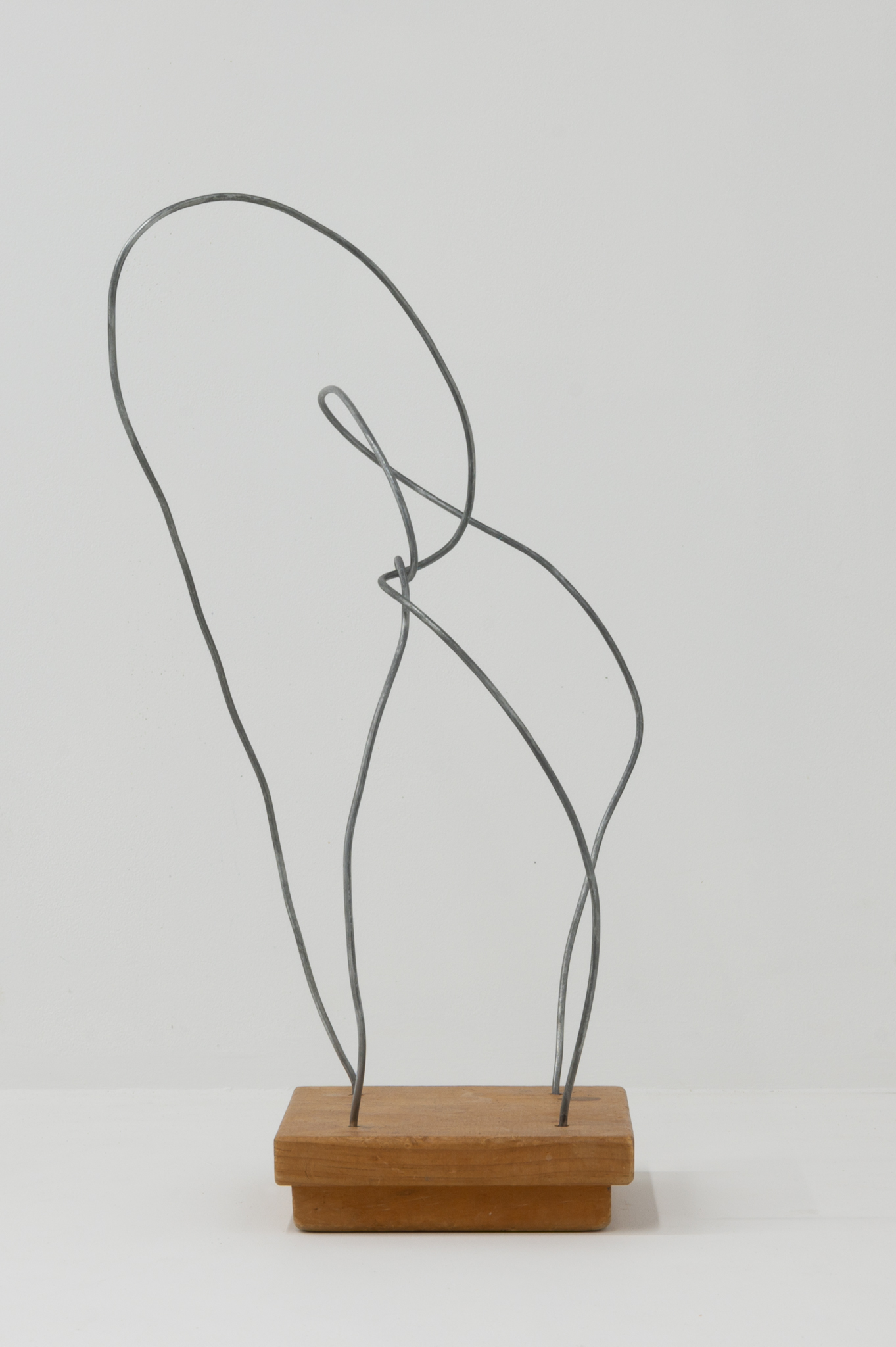

Rex Veal & Olive, 'Sun'.

3 - 18 Feb 2024

Fulfilling the Beyond Here and Now

Naming suffering, exalting it, dissecting it into its smallest components — that is doubtless a way to curb mourning. To revel in it at times, but also to go beyond it, moving on to another form, not so scorching, more and more perfunctory… Nevertheless, art seems to point to a few devices that bypass complacency and, without simply turning mourning into mania, secure for the artist and the connoisseur a sublimatory hold over the lost Thing. First by means of prosody, the language beyond language that inserts into the sign the rhythm and alliterations of semiotic processes. Also by means of the polyvalence of sign and symbol, which unsettles naming and, by building up a plurality of connotations around the sign, affords the subject a chance to imagine the nonmeaning, or the true meaning, of the Thing. Finally by means of the psychic organization of forgiveness: identification of the speaker with a welcoming, kindly ideal, capable of removing the guilt from revenge, or humiliation from narcissistic wound, which underlies depressed people's despair.

Can the beautiful be sad? Is beauty inseparable from the ephemeral and hence from mourning? Or else is the beautiful the one that tirelessly returns destructions and wars in order to bear witness that there is survival after death, that immortality is possible? Freud touches on those matters in a brief essay, "On Transience" (1915-1916), inspired by a discussion during a stroll with two melancholy friends, one of whom was a poet. To the pessimist who depreciated the beautiful on the ground that its ephemeral fate led to a decrease in value Freud retorted, "On the contrary, an increase!" The sadness that the ephemeral gives rise to, however, seemed to him unfathomable. "To the psychologist, mourning is a great riddle.... But why is it that this detachment of the libido from its objects should be such a painful process is a mystery to us and we have not hitherto been able to frame any hypothesis to account for it."

Shortly afterwards, in Mourning and Melancholia (1917), he offered an explanation for melancholia, which, following the model of mourning, would be caused by the introjection of the lost object, both loved and hated, that I discussed earlier. Here, however, in the essay "On Transience," by linking the themes of mourning, transience, and beauty, Freud suggested that sublimation might be the counterpoise of the loss, to which the libido so enigmatically fastens itself. Enigma of mourning or enigma of the beautiful? And what is their relationship? Admittedly invisible until mourning for the object of love takes place, beauty nevertheless remains and, even more so, enthralls us. "Our high opinion of the riches of civilization has lost nothing from our discovery of their fragility." There might thus be something that is not affected by the universality of death: beauty?

Might the beautiful be the ideal object that never disappoints the libido? Or might the beautiful object appear as the absolute and indestructible restorer of the deserting object? That could be due to its having placed itself at once on a different level of the libidinal territory, so enigmatically clinging and disappointing, where the ambiguity of the “good” and “bad” object is displayed. In the place of death and so as not to die of the other’s death, I bring forth — or at least I rate highly — an artifice, an ideal, a “beyond” that my psyche produces in order to take up a position outside itself — ek-stasis. How beautiful to be able to replace all perishable psychic values.

Since then, however, analysts have asked themselves an additional question: by means of what psychic process, through what alteration in signs and materials, does beauty succeed in nuking its way through the drama that is being played out between the lass and the mastery over the self’s loss/devalorization/execution?

Sublimation's dynamics, by summoning up primary processes and idealization, weaves a hypersign around and with the depressive void. This is allegory, as lavishness of that which no longer is, but which regains for myself a higher meaning because I am able to rebuke nothingness, better than it was and within an unchanging harmony, here and now and forever, for the sake of someone else. Artifice, as sublime meaning for and on behalf of the underlying, implicit nonbeing, replaces the ephemeral. Beauty is consubstantial with it. Like feminine finery concealing stubborn depressions, beauty emerges as the admirable face of loss, transforming it in order to make it live.

A denial of loss? It can be so; such beauty is then perishable and vanishes into death, unable to check the artist's suicide, or else fading away from memory at the very moment of its appearance. But not only that.

When we have been able to go through our melancholia to the point of becoming interested in the life of signs, beauty may also grab hold of us to bear witness for someone who grandly discovered the royal way through which humanity transcends the grief of being apart: the way of speech given to suffering, including screams, music, silence, and laughter. The grandiose would even be the impossible dream, the depressive's other world, fulfilled here below. Outside the depressive space, is the grandiose anything but a game?

Sublimation alone withstands death. The beautiful object that can bewitch us into its world seems to us more of adoption than any loved or hated cause for wound or sorrow. Depression recognizes this and agrees to live within and for that object, but such adoption of the sublime is no longer libidinal. It is already detached, dissociated, it has already integrated the traces of death, which is signified as lack of concern, absentmindedness, carelessness. Beauty is an artifice; it is imaginary.

Excerpt from Julia Kristeva, “Beauty: The Depressive’s Other Realm,” in Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987): 97–100.